- Home

- News & Events

- News Blog

- Lessons from Auschwitz

Lessons from Auschwitz

News

News

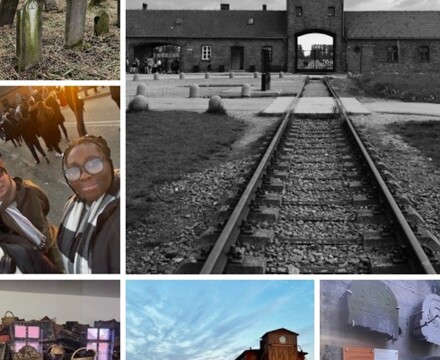

In October 2024 two students from St Charles Sixth Form College Laura Chukwueke and Ava Mogaji were selected to participate in the Lessons from Auschwitz project, organised through the Holocaust Educational Trust. Both students, who are studying for their A levels at St. Charles, felt honoured to represent the College in this unique educational experience, alongside approximately 200 other students from schools and colleges in the South London region. They were accompanied by staff member Jordan Macedo.

Throughout the project, the two girls were really excellent ambassadors for the College. Although it was a challenging experience, due to its intense emotional impact, they found it utterly rewarding, stating that it was a fantastic opportunity and a journey of learning and exploration - not just about the history of the Holocaust but also the world we live in.

Below you can read their recollections of their involvement in this amazing educational programme.

Laura Chukwueke:

“My journey to Poland generated elements of both numbness and grief within me. Being able to witness first-hand the horrors human beings caused to millions of other human beings was horrendous and hard to comprehend. Touring the different rooms looking at the representations of all the individual lives of the Jewish people and others that had been torn apart in the holocaust, shone a light on the significance and value of each and every one of their lives. Before this project, I didn’t really have a wide scale understanding of what pre-war Jewish life looked like and how unique their lives were but having gone there, I was able to see that the treasure that is life itself had been snatched ruthlessly away from them. Their possessions all on display in front of us; their suitcases, clothes, shoes, glasses, hair representing each individual that died in this treacherous genocide sent a chill down my spine. Although I only had a vague idea of what happened in the holocaust before my visit to the concentration camps, this trip helped me get a deeper understanding of what inconceivable suffering the people had to go through and how they must have felt in these camps. The horror that all these people must have went through was unimaginable. It was especially sickening when we went to the buildings where the bedrooms were and where the gas chambers were, it just hurt to see that so many people were crammed into these small places to be killed. It was equally disturbing when we entered the room with all the names of those who were mercilessly slaughtered; there were so many pages of people’s names showing the mass destruction of a race of people which made me feel numb to the core. What really, really got to me was the number of children that lost their lives. I could only imagine the fear in their eyes as they wondered why these things were happening all around them, their families.

There were specific memorials we went to during the visit. The first was in a cemetery where there were what seemed like thousands of pieces of grave stones everywhere with each of them having a name and related occupation in Hebrew written on them. There were many lives that did not have a grave stone to mark them but who also needed commemorating and remembering there and then. When we gathered for the final memorial at the end of our visit and the Rabbi said a few words of prayer, it gave me encouragement to never give up even when things get tough because there is always someone else out there fighting a stronger battle and the holocaust survivors and their life stories are an inspiration to every single one of us especially in the world we live in today.

The Lessons from Auschwitz project was a unique opportunity for me to properly understand that this was more than just statistics in a history chapter and instead the annihilation of countless individual lives and stories of which we should always remember and prevent from happening in the future."

Ava Mogaji:

“First of all, I will start with acknowledging that to be chosen out of many other students to take part in a project such as Lessons from Auschwitz was an honour of which I am immensely thankful for and will certainly not forget. The project started off with some online tasks of which involved learning about pre-war Jewish life across Europe, informing us on Jewish life across different societies before the holocaust and learning about some personal experiences from victims of the holocaust.

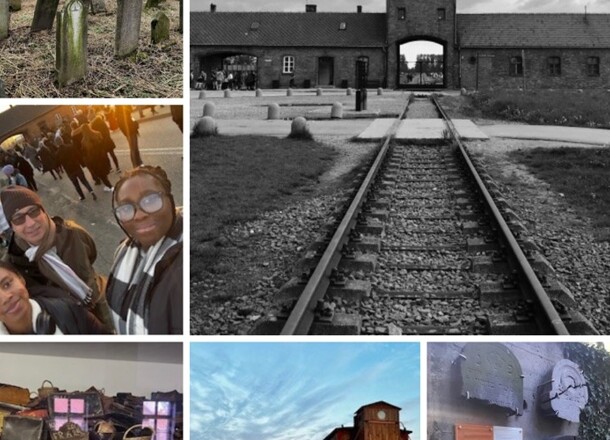

Then on our day visit to Poland, we visited three main sites, Auschwitz I, Auschwitz-Birkenau, as well as a Jewish cemetery in the town of Oswiecim, where the German name of ‘Auschwitz’ was derived from. Our first visit was to the cemetery, and although cemeteries aren’t typically associated with positive feelings, it particularly hurt to visit this one. Oswiecim used to have a large population of Jewish people, making up 58% before the outbreak of the war, peacefully living alongside the Christian community. However, all the Jewish people that once inhabited Oswiecim have since died or relocated, meaning that these graves often aren’t visited by relatives and remain neglected as a result. Before leaving the cemetery, a Rabbi from the Western Marble Arch synagogue spoke to us about the cemetery and the history of the Jewish people in Oswiecim, but also gave us an explanation of the Jewish perception of death. The Jewish outlook is different to that of which some people share, with Jewish people viewing death as a ‘positive’ thing. This was because they believed that death itself wasn’t the end and that their souls live on forever.

After that, we travelled to the two different Auschwitz sites, where we received a tour of different areas by a tour guide. Before going on this trip, we were warned that this would be an emotionally intense experience, however I don’t think it's easy to imagine that until you are actually there. I recall everyone in our tour group remaining either super quiet or silent for the entire tour, a testament to how shocking it truly was. A room that particularly saddened me was a room with a bunch of pots and pans – Jewish people thought that they would be able to cook in the camps. Instead, they were served rations, and many died of starvation or illnesses stemming from starvation.

Throughout the project, there has been a constant emphasis on the idea of humanizing the victims of the holocaust and using personal stories when discussing our findings and to not just focus on statistical figures. When back from the trip, we took part in an additional online seminar in which we were able to witness a holocaust victim’s personal testimony of his experiences during and after the war. Although his experiences of the holocaust were horrifying to say the least and he was grateful that the persecutors were gone, John insisted that he did not hate them, believing that hate is ‘corrosive’ and asking us not to include hate against anyone, including the persecutors but also to not allow in our circle any discrimination and hatred and to stand up against it. I admired his positive outlook despite all he and his family have gone through, and this experience has helped me recognize how complex the Holocaust truly was and has reaffirmed the idea that if we do not challenge hatred within society, it can result in horrifying consequences. Therefore, it is important that we challenge any forms of hatred we encounter and that we do not let historical tragedies such as this one be forgotten."

Jordan Macedo (Deputy safeguarding Lead)

“I would also like to share my account to try and unravel the massive effect the trip to Auschwitz-Birkenau has had on me. As someone with a love for the past and how it’s been shaped by so many people and events over time, I appreciate it can be quite easy to simply get lost in these past events and forget but this trip has furthered my resolve to make sure the Holocaust is not only remembered, but learnt from so the same mistakes are not made ever again.

Before I visited Auschwitz, I wasn’t aware that there were Holocaust deniers; people who denied that the holocaust ever took place. The fact that I am still part of the generation who will have the honour of hearing a Holocaust speaker at first hand is humbling. As part of the programme we met virtually with a holocaust survivor and from their open and stark testimony, it was clear that their suffering was horrendous and unimaginable, and very real. Sitting at my desk listening to what John was sharing with us, I could not take my eyes off the screen for one second as his presence held so much power; his life story was so, so powerful and poignant. I am aware that the Holocaust is extraordinarily hard to take in and understand but listening to what he was saying, all I could do was to accept the harsh realisation of the atrocities that had been committed.

Our first stop on a Day trip to Auschwitz was a visit to Jewish Cemetery in Oświęcim:

‘The Jewish cemetery in Oświęcim (German: Auschwitz), Poland, was destroyed by the Germans during World War II and partly restored by returning Jewish survivors after the Holocaust. In Communist Poland it fell into disrepair and was fully restored in the 1990s.

About 1,000 tombstones (Hebrew: matzevot) with Hebrew, German, Polish and Yiddish inscriptions survived to this day. The last person to be buried here is Szymon Kluger (1925-2000).’

My visit to the cemetery left me wondering how it was so easy for the German army to destroy a shrine to a civilisation, people who had peacefully buried their loved ones here so they could visit and remember their lives. It was great to see that through hard work and donations, extensive renovations including a new wall and entrance gates have been carried out. Talking to one of the guides she said “Oswiecim feels like a body with no soul”. There were no remaining signs of any Jewish life or culture in the town and as the ground grew muddy on the land that once held the greatest synagogue in that town, I felt a real sense of sadness and grief.

The second stop on our visit was The Auschwitz-Birkenau Museum and Memorial:

‘The Archives of the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum in Oświęcim collect, preserve, and provide access to archival materials connected mostly with the history of Auschwitz Concentration Camp, and to a lesser extent with other concentration camps as well. The collection includes original German camp records, copies of documents obtained from other institutions in Poland and abroad, source material of post-war provenance (memoirs, accounts by former prisoners, material from the trials of Nazi war criminals, etc.), photographs, microfilms, negatives, documentary films, scholarly studies, reviews, lectures, exhibition scenarios, film scripts, and search results.’

Walking thorough the grounds of the Museum you feel totally stripped of any notion you might have of humanity. Listening to the guide telling the stories, viewing all the pictures, displays and the expressions on visitors’ faces of the true horrors that happened here you can’t help but to feel lost and lonely. As a young man fascinated by history and wanting to know how it shaped our future, I left wondering how people could be so evil and inflict such horrors on others. But when the true facts are laid bare before you, it’s impossible to ignore or even begin to understand the reasons for the atrocities that were carried out in Auschwitz-Birkenau. The most horrific of it all, was the pain inflicted on children either through carrying out experiments or just because they were defenceless. It’s believed that, on the basis of the partially preserved camp records and estimates, that there were approximately 232 thousand children and young people up to the age of 18 among the 1.3 million or more people deported to the Auschwitz-Birkenau camp. This figure includes about 216 thousand Jews, 11 thousand Roma, at least 3 thousand Poles, over 1 thousand Belorussians, and significant numbers of Russians, Ukrainians, and others. The majority of them were deported to Auschwitz along with their parents in various campaigns directed against whole ethnic or social groups. Slightly more than 23.5 thousand children and young people were registered in the camp, out of the total of 400 thousand registered prisoners.

I admit that I was filled with rage a lot of the time during the trip to Poland; the utter disregard for other human life deeply shocked and angered me. Seeing the possessions of the victims on display; their suitcases, glasses, shoes, highlighting their former lives and the nail marks in the glass chambers horrified me to the core. It all brought home to me, unlike any text book possibly could, the humongous annellation caused by this catastrophic genocide and at that moment keeping the memory alive of this and subsequent genocides worldwide, had never felt so important to me.

The Third stop on our visit was Birkenau, a purpose-built extermination camp where mainly Jewish and Roma (or ‘Gypsy’) prisoners were murdered.

When I first caught a glimpse of Auschwitz-Birkenau, my stomach immediately dropped and I began to dread what I was about to experience. The feeling here was different to the town, Auschwitz. It felt like a man-made factory, oiled and primed to work like clockwork and it brought closer to my mind the isolation and despair it would have felt like to exist and be forced to work under horrific and brutal conditions here. This feeling only grew stronger within me when I saw the horrific beginnings of an unfinished Birkenau, clear for all to notice that the workforce was one of manufacturing death. The ‘buildings’ which housed the victims made me feel as if I was disrespecting their memories by being there, I felt uncomfortable standing there and the realisation of the barbaric conditions these prisoners were forced to live in, offering no shelter or dignity of any kind, made me shiver within. The camp at Birkenau is one of many extensions to Auschwitz that were built to accommodate more prisoners – and it is by far the biggest. It is here that the extermination reached its most horrifying and industrial scale. There were four gas chambers and crematoriums at the peak and the majority probably about 90% of the victims of Auschwitz died in Birkenau. This was approximately a million people. The majority, more than nine in ten, were Jews.

Before I set out on my day visit to Auschwitz I read the book ‘The Happiest Man on Earth’, the beautiful life of an Auschwitz Survivor, born in Leipzig Germany. I wanted to know more of its history, a true account from someone who had been there and survived its Evil.

After reading the book and watching his lecture on YouTube, it gave me an insight into what to expect and prepared me for what was a very challenging day, not only physically but also mentally. Nothing however could have prepared me or anyone that visits for the inhumane and horrific story we were about to hear and experience. Visiting Auschwitz Birkenau truly put things into perspective for me. I am incredibly lucky to be born in the 60’s in a forward-thinking society, and to have had endless opportunities and autonomy. Yes, life can seem difficult and overwhelming at times, but the fact that I live in a free society, is something I will be forever grateful for. The Holocaust ended, but antisemitism and other extreme forms of racism and wars are still occurring on a daily basis. It is crucial that we raise awareness of the Holocaust in order to prevent repetition in the future. The seeds of the Holocaust began sprouting long before the massacres and death camps. It was the dismissal of relatively minor anti-Semitic acts which allowed room for the rise in antisemitism. Standing by in silence made it possible for the Holocaust to happen, when the final solution occurred, it was too late to speak up. I find it challenging, frustrating and depressing that man’s inhumanity to man seems innate but in Eddie Jaku own words: ‘If enough people had stood up then, on Kristallnacht, and said, ‘Enough! What are you doing? What is wrong with you?’ then the course of history would have been different. But they did not. They were scared. And this allowed them to be manipulated into hatred.

Sadly, for me my last reflection is so harrowing; it is not just the scale of the atrocity, but its deliberate execution. It forces us to confront the darkest capacities of humanity, hatred, indifference and complicity. At the same time, the stories of resistance, solidarity and faith within the camps reveal the resilience of the human spirit even in the face of annihilation. Each barrack, gas chamber, and train track bore witness to countless lives snuffed out, men, women and children, stripped of their dignity and reduced to numbers. As I sit with my reflection the weight of the loss feels unbearable, yet remembering ensures that we remain vigilant against the seeds of such hatred.”